What the Apple TV+ series reveals about the false separation between who we are inside and outside of work

The Unsettling Truth Severance Reveals About Us

There’s something deeply unsettling about Severance—and it’s not just the sterile aesthetic of Lumon or the dystopian tension that lingers in its hallways. The real discomfort comes from somewhere else: the realization that by brutally separating the “work self” from the “outside self,” the show exposes a dynamic that’s all too familiar. The self-division in Severance is, in fact, a reflection of the compartmentalization we already experience in real life. The series doesn’t just create a provocative fiction—it surgically reveals something we are already part of.

Series creator Dan Erickson has said the idea came to him during a mundane temp job, when he found himself wishing he could “skip the next eight hours of his life.” Out of that disturbing fantasy, a premise was born: what if it were literally possible to erase the workday?

Read more: Dan Erickson on Severance – How the Series Was Created

The False Separation Between Our Selves

At first glance, Lumon’s proposal seems absurd: to create two distinct versions of a single person, each confined to one side of life. But look closer and it’s clear this radical experiment isn’t far from modern reality. We’re taught early on to compartmentalize our existence. A professional self—efficient and emotionless. A personal self—affectionate, creative, and exhausted. And between them, a chasm.

This article looks at Severance not as a dystopia of the future, but as an unsettling metaphor for the present. What if the show isn’t trying to convince us we can have two minds—but rather warning us that we already live as if we do? What if the characters’ reintegration isn’t just a narrative solution but a real call to stop living fractured lives?

Compartmentalization Is Not Fiction. It’s Routine.

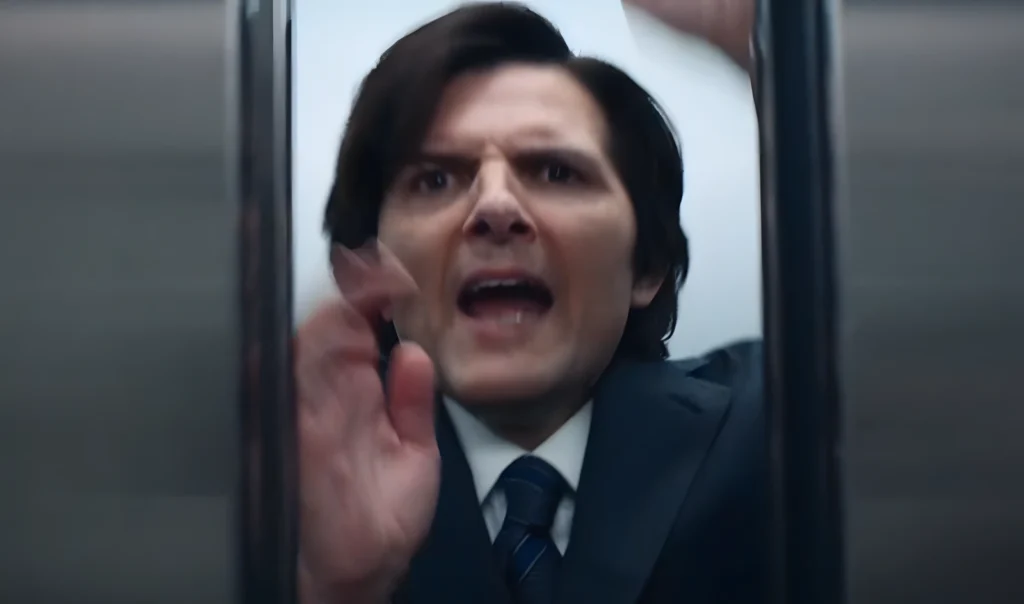

Helly R arriving at Lumon for her shift as an Innie.

What Lumon proposes with its severance procedure is just an extreme version of what work culture silently demands: that we leave our conflicts, pains, and emotions at the office door. Worse, that from 9 to 5 we perform a social role disconnected from who we are outside.

You don’t need a chip in your brain to live divided. All it takes is a badge, an unreachable target, and the fear of seeming weak.

The show merely lays bare what we’ve normalized for the sake of convenience or survival. When Helly tries to kill herself to escape her corporate prison, she’s not just desperate—she’s responding to a reality many of us feel but have internalized as anxiety, apathy, or burnout.

Four Characters, One Shared Fracture

When we observe the characters in Severance, we don’t see absolute heroes or villains—we see fragments.

Helena Eagan

Her outie enters the experiment as a marketing strategy and manipulates her Innie like a pawn. Yet it’s this pawn—Helly R—who becomes the series’ most visceral rebellion. She rejects the role, defies obedience, and screams for wholeness. There are not two people here—just one, torn between convenience and a desire for freedom.

Mark

The protagonist represents numbed grief. Outside, he drinks and runs on autopilot to avoid confronting the death of his wife. Inside, he lives in functional emptiness, unaware of why. But gradually, the two halves start to bleed into each other. When he discovers that Ms. Casey is his wife Gemma, the fracture becomes unbearable. Reintegration is no longer a choice—it’s a necessity.

Dylan

The most impulsive of the group experiences the quietest transformation. He briefly sees his son from the outside world—and that spark of emotion is enough to reshape his relationship with work. What was once a game of rewards becomes an emotional prison. He wants out. He wants to be whole.

Irving

He lives the split as ritual. Loyal to Lumon, devoted to rules, he embodies the Innie who seeks meaning within the system. At first glance, he seems resigned. But externally, he starts to break: recurring dreams of dark hallways, forbidden memories, emotions that cross the boundary. In this quiet unraveling, Irving represents the slow collapse of the archetype—the moment when even the most conforming begins to long for wholeness.

Self-Division in Severance and the Illusion of Separate Selves

In fan discussions, characters are often judged as if their Innie and Outie versions were completely different people. Helly is the hero, Helena the villain. Innie Dylan is brave, Outie Dylan is weak. But this interpretation, while understandable, may be mirroring the very mechanism Lumon enforces: the moral division of the self.

There are not two people. There is one. Conditioned, mutilated, adapted to each environment.

Perhaps the show’s real provocation is this: what if the idea of compartmentalizing our identity isn’t just harmful but a convenient lie? A way of not admitting that we are contradictory, incoherent, simultaneously free and domesticated?

Reintegration: The Name of Real Freedom

In the world of the series, reintegration is seen as dangerous. A mental collapse. A threat to order. And it is all of those things. Because to integrate who we are is an act of deep courage.

Reintegration means accepting that even the parts we avoid are ours. That fear, anger, guilt, indifference, and conformity also bear our signature. It means no longer using the “work self” as an excuse for choices that violate us. It means saying no to a system that demands we be less in order to function.

Conclusion: Stop Living Fractured

Severance isn’t asking whether we want to join a dystopian experiment. It’s asking if we’re already in one. What if what we accept as normal is just socially accepted alienation dressed as productivity?

Self-division in Severance is disturbing precisely because it doesn’t feel far off—it’s a radical portrayal of what many already live in silence: a fragmented life.

Maybe the future we should fear isn’t one where chips are implanted in our brains—but the one where we stop feeling like we are a whole person.

So perhaps the real severance we need now is from the idea that there’s a part of us we can leave outside.

Integration, then, isn’t a problem to be avoided. More than that, it’s the freedom we’ve forgotten to want.

Keep exploring the hidden meanings of Severance:

- Dan Erickson and the Origin of Severance: The Fantasy That Became a Critique of Work Culture

- Helena Eagan in Severance: The Heiress Who Lost Everything

- Helly (Britt Lower): The Embodied Resistance of Severance

- Dylan in Severance (Zach Cherry): The Irreverent Spark That Challenges the System

- Lumon Mythology: Symbols, Doctrine, and the Rituals of the Corporate Cult

Posts Recomendados

Carregando recomendações...