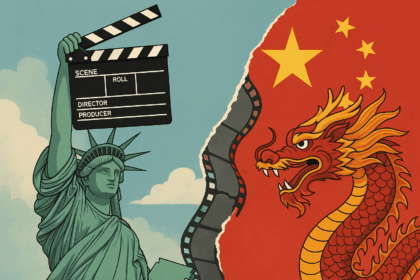

Hollywood could lose China. The phrase may sound like an exaggeration, but it captures a growing fear of a new crisis in the global film industry. With Donald Trump’s return to power, the reintroduction of tariffs against China has reignited trade tensions — and there’s already talk of a potential retaliation: a total ban on American movies.

If confirmed, such a move would have a direct impact on global cinema. At a time when the industry is still recovering, losing access to the world’s second-largest film market could disrupt the strategies of major studios, slash billion-dollar revenues, and even jeopardize future productions.

The Weight of China for Major Studios

Although American films have lost some ground in China in recent years, the country still represents a significant share of global box office revenue. In 2024, for instance, Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire grossed $132 million in China alone. Alien: Romulus made over $110 million in the Chinese market. Even mid-budget releases like The Beekeeper earned more than $16 million thanks to Chinese audiences.

Hollywood solidified its presence in China following the country’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, which allowed for limited imports of foreign films. Since then, that number has gradually increased: by 2012, the annual cap had reached 34 films. More recently, in 2024, China screened 93 international features — the highest number since 2019 — and, in a symbolic move, officially reopened its doors to Hollywood in January 2025.

However, this renewed engagement has always been on shaky ground. The Chinese government continues to impose strict censorship and regulations, and U.S. studios receive only about 25% of gross box office revenue in the country — a far smaller share than in other markets.

An Unfavorable Economic Landscape

The potential exclusion of China from Hollywood’s circuit comes just as the global film industry is still trying to stabilize after years of disruption. Hollywood could lose China, and the consequences go far beyond ticket sales. The pandemic closed theaters for extended periods and delayed major releases. Then, the writers’ and actors’ strikes of 2023 brought productions to a halt for months.

In 2025, despite some promising debuts — such as The Minecraft Movie, which pulled in $314 million globally on opening weekend — performance in the U.S. remains roughly 5% below what it was during the same period in 2024. Consequently, cutting China out of the equation means losing a strategic counterbalance to domestic market decline.

And that’s not all: the impact of Trump’s tariffs on cinema could also hit consumers. A recent study by Yale University estimated that the tariffs could raise annual household expenses by up to $4,200. In tough economic times, entertainment is often one of the first expenses to be cut.

With ticket prices already high — and expected to climb even further — going to the movies may cease to be a priority for many people, especially families. In this scenario, if the trend continues, studios will likely have to rethink not just the volume, but also the type of films they produce.

Beyond the Box Office: A Domino Effect

Even though Hollywood’s dependence on China has declined recently, Hollywood could lose China — and losing this market now would be more than a financial setback. It would be a wake-up call for the entire entertainment production chain. Studios plan high-budget films, like Avatar: Fire and Ash, with global appeal in mind. And while they may not rely entirely on the Chinese market, eliminating that possibility altogether could hurt profitability.

Scene from the movie Avatar Fire And Ash

In practical terms, this could mean:

- Fewer blockbusters being greenlit;

- Job losses in the creative sector;

- Cuts to international marketing campaigns;

- Changes in film themes to avoid political friction.

A Trade War with Cultural Fallout

The impact of Trump’s tariffs on cinema isn’t just about money. It’s also about how political decisions shape what the world consumes as culture. When geopolitical tensions prevent certain films from reaching strategic markets, there’s a symbolic and creative loss that goes far beyond economics.

The film industry has already proven its ability to reinvent itself. But the exclusion of China, combined with internal economic pressures, may require deeper adjustments — both in business models and storytelling approaches.

And perhaps the greatest challenge isn’t in the numbers, but in how global culture fragments when bridges between nations begin to collapse.

In a world where politics increasingly interferes with art, can cinema still unite what geopolitics insists on dividing?

Keep exploring the industry’s behind-the-scenes:

Posts Recomendados

Carregando recomendações...